The "10x engineer" has become Silicon Valley shorthand for exceptional talent - someone who produces ten times the output of an average developer. After decades in this industry, I've worked alongside people who genuinely produced at that level. The phenomenon is real. The myth is everything we've built around it.

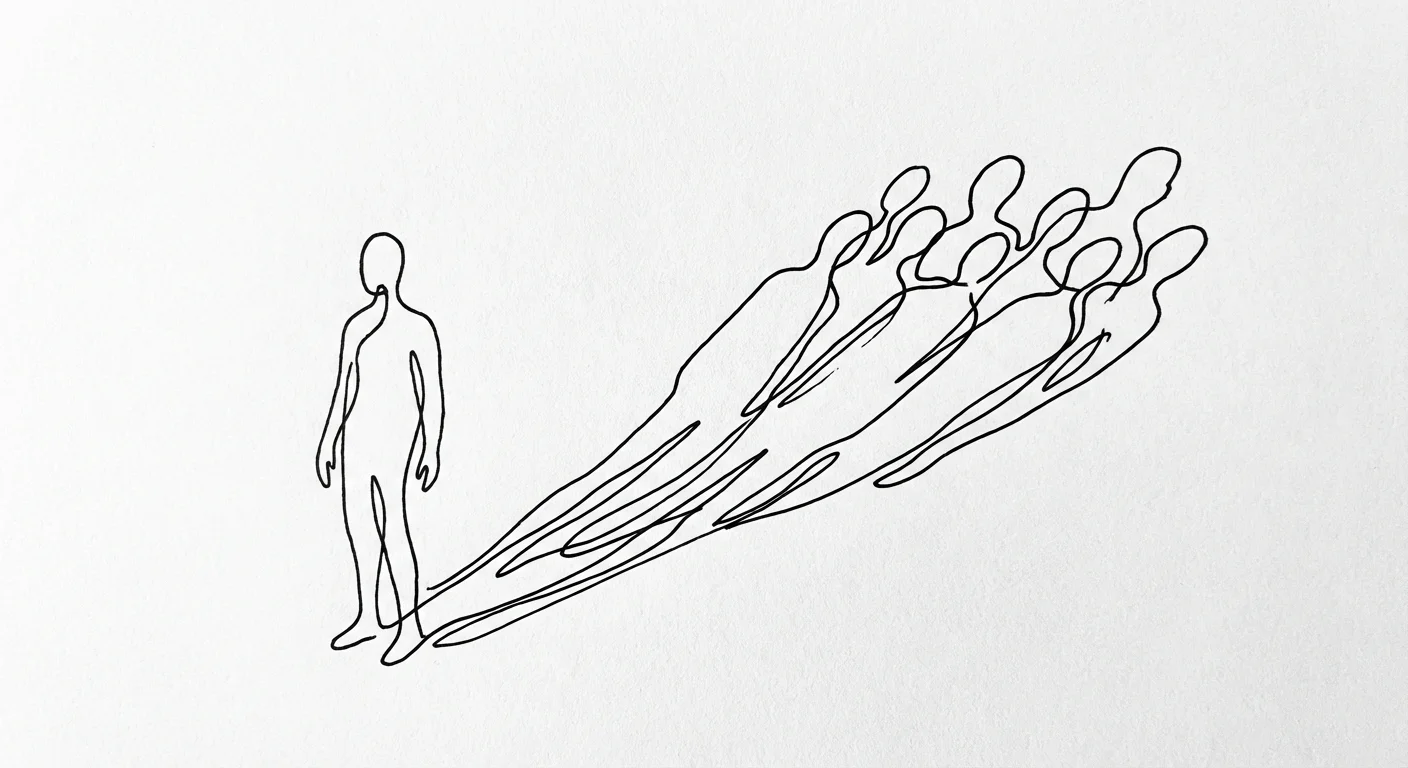

Stop hunting for 10x engineers. Build systems that make average engineers effective. Team multipliers beat individual heroics.

It makes sense why this belief persists—there's a kernel of truth to it.

The problem isn't whether exceptional engineers exist. They do. The problem is how the industry tries to identify, hire, and deploy them - and the damage these misconceptions cause to teams and organizations.

What the Research Actually Shows

The 10x claim traces back to studies from the 1960s and 1970s, most notably the 1968 work by Sackman, Erikson, and Grant, and later by Tom DeMarco and Tim Lister in "Peopleware." These studies measured programming tasks and found large variations in individual performance.

What they actually found:

- Variation exists. Some programmers complete tasks dramatically faster than others. This is real and measurable.

- The gap is real. A 10:1 or higher ratio between the slowest and fastest programmers is not unusual.

- The tasks were isolated. Studies measured individual coding exercises - but real-world impact includes architecture, debugging, and making others more effective.

The research is valid. But as Carnegie Mellon's SEI notes, the way the industry has interpreted and weaponized these findings has created more problems than it solved.

Where High Productivity Actually Comes From

Having observed high-performing engineers over many years, the patterns are consistent. It's not about typing faster:

- Pattern recognition from experience. Seeing problems before helps avoid dead ends. Experience builds a library of "what doesn't work."

- Architectural intuition. Knowing what will scale and what won't, before writing code. Getting the foundation right means less rework later.

- Tool mastery. Deep knowledge of languages, frameworks, and development environments eliminates friction.

- Problem decomposition. Breaking complex problems into solvable pieces quickly, without getting lost in complexity.

- Knowing what not to build. The fastest code is code you don't write. Recognizing when existing solutions work saves enormous time.

None of this is magic. It's accumulated knowledge and deliberate skill development over years. Anyone willing to invest time and stay curious can develop these capabilities.

The Misuse of 10x

The damage comes from how organizations try to find, use, and measure exceptional engineers:

- "We'll hire 10x engineers instead of a team." One person, no matter how productive, can't parallelize. Can't be in two meetings. Can't take vacation without stopping progress.

- Measuring by commits or lines of code. The highest-impact work often involves deleting code or designing systems that prevent code from needing to be written at all.

- Expecting 10x from everyone. Job postings seeking "rockstars" usually mean "we want exceptional output at average wages with no support structure."

- Confusing speed with impact. A fast engineer building the wrong thing creates negative value. Architecture and direction matter more than velocity.

High-performing engineers are force multipliers when used correctly - and bottlenecks when organizations misunderstand what makes them effective.

Common Traits I've Observed

The engineers who consistently produce at high levels share traits that aren't what most people expect:

- They've failed extensively. Decades of mistakes create pattern libraries. They know what doesn't work because they've tried it.

- They maintain focus. Context-switching destroys productivity. High performers protect their focus aggressively.

- They understand the full stack. Knowing what happens from user click to database write eliminates guessing where problems lie.

- They build for maintenance. Code written to be understood later is faster to debug, extend, and hand off.

- They communicate effectively. Clear documentation, good commit messages, and explicit architecture decisions multiply impact.

- They know when to say no. High performers avoid low-value work and premature optimization. They focus energy on problems that actually matter.

- They automate ruthlessly. Repetitive tasks get scripted immediately. This frees time for problems that require human judgment.

These skills compound over time. But they're learnable. The gap between "average" and "exceptional" often comes down to deliberate practice and curiosity.

What separates experienced engineers from novices isn't innate talent - it's accumulated judgment about which problems deserve attention and which solutions will hold up. That judgment comes from building systems, watching them fail, and learning what fragility looks like.

The Team Destruction Pattern

Organizations make predictable mistakes when they identify a high performer:

- They route everything through them. Creating a bottleneck that negates the productivity advantage.

- They stop developing others. "Just give it to [high performer]" means juniors never learn.

- They create dependencies. When the key person leaves, institutional knowledge leaves with them.

- They burn them out. Engineers who carry everything eventually break or quit.

- They reward them with management. The best individual contributor becomes the worst manager, losing both their contributions and team morale.

The correct approach is to have experienced engineers design systems, establish patterns, and mentor others - not to have them write all the code themselves.

I've seen companies lose high performers not because competitors paid more, but because workload became unsustainable. When one person is responsible for too many critical systems, they can't take vacation or focus on interesting problems. Organizations destroy their highest performers by relying on them too heavily.

Measuring the Wrong Things

Attempts to identify or measure exceptional engineers fail because they measure the wrong things:

- Lines of code. Sometimes the highest-impact contribution is a 50-line refactor that prevents 10,000 lines of technical debt.

- Commits per day. Encourages small, meaningless commits rather than thoughtful, complete changes.

- Story points. Rewards point inflation and gaming rather than actual value delivery.

- Interview performance. Whiteboard coding tests measure interview preparation, not engineering capability. As I've written about, technical interviews are fundamentally broken.

The engineers who create the most value are often invisible to these metrics. Their impact shows up in system reliability, team velocity, and problems that never occur because good architecture prevented them.

When Seeking 10x Engineers Makes Sense

I'm not saying the search for exceptional engineers is always misguided. It makes sense when:

- You have a genuinely hard technical problem. Some challenges require deep expertise that average engineers can't provide. Compiler optimization, distributed consensus, ML infrastructure - certain problems need specialists.

- You're building a small founding team. In a 3-person startup, each hire matters enormously. One exceptional engineer can set architectural patterns that scale for years.

- You can actually support them. If you have autonomy, interesting problems, and competitive compensation, high performers will thrive. Without these, they'll leave.

But for most engineering organizations, building reliable teams matters more than finding unicorns. Ten competent engineers with good collaboration beat one genius working alone.

10x Environment Audit

Score whether your organization enables or destroys high performers:

What Actually Works

Organizations that successfully leverage high performers do things differently:

- They evaluate real work. Code reviews of actual projects, system design discussions, past architecture decisions.

- They check references deeply. Not "did they work there?" but "what did they actually build and how did it perform?"

- They look for track records. Systems that scaled, products that shipped, problems that got solved.

- They provide autonomy. High performers produce exceptional work when given clear goals and room to operate.

- They invest in everyone. Building a culture of learning raises the entire team rather than depending on a few stars.

The search for 10x engineers fails when organizations want the output without providing the environment that makes it possible.

Engineering Environment Health Scorecard

Score whether your environment enables high performance. Low scores mean even exceptional engineers will underperform.

| Dimension | Score 0 (Suppresses) | Score 1 (Neutral) | Score 2 (Enables) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Focus Time | Constant interruptions | Some protected time | 4+ hours uninterrupted daily |

| Autonomy | Approval required for everything | Some discretion | Clear goals, freedom in approach |

| Technical Quality | Ship fast, fix never | Quality when time permits | Quality is non-negotiable |

| Knowledge Sharing | Heroes hoarded, silos rewarded | Ad-hoc mentoring | Systematic cross-training |

| Failure Tolerance | Blame culture | Mistakes tolerated | Failures are learning opportunities |

| Measurement Focus | Lines of code / commits | Mixed metrics | Outcomes and impact |

The Bottom Line

Large variations in engineering productivity are real and measurable. The research confirms what anyone who's worked on enough teams has seen firsthand.

What's mythical is the belief that coding tests reliably identify them, that one exceptional engineer replaces a team, or that any organization can just "hire 10x" and solve their problems.

The better approach: create environments where engineers can do their best work, build systems that don't depend on heroics, and invest in developing everyone. The obsession with unicorns distracts from building functional teams.

"The fastest code is code you don't write."

Sources

- Construx: The Origins of 10X - How Valid Is the Underlying Research? — Steve McConnell's analysis of the original studies

- Peopleware: Productive Projects and Teams — DeMarco and Lister's research on software team productivity

- IEEE: Programmer Performance and the Effects of the Workplace — Academic research on programming productivity factors

Build Effective Teams

Hiring, team structure, and engineering culture. Advice from someone who's built and scaled engineering organizations.

Let's Talk