Segment's microservices rewrite cost millions and ended with them returning to a monolith after 3 years. After explaining why microservices are often a mistake, I owe you the flip side: when they actually work. Over two decades of building distributed systems, I've seen both architectures succeed and fail. The microservices that succeeded shared characteristics that had nothing to do with following trends.

Adopt microservices only when you have: 20+ engineers, genuinely different deployment cadences, and proven scaling bottlenecks. Start with a modular monolith.

The question isn't whether microservices are good or bad. It's whether your situation matches the constraints they solve. Most teams don't —but some genuinely do.

The Complexity Budget

Here's a mental model that clarifies most architecture decisions: every startup has a "Complexity Budget" of 100 points. Spend them wisely, because you can't get more.

- A monolith costs 10 points. You understand it. It deploys simply. Debugging is straightforward.

- Kubernetes costs 40 points. Now you're managing cluster state, networking, secrets, and YAML that nobody fully understands.

- Distributed tracing costs 20 points. Because you can't debug distributed systems without it.

- Service mesh costs 15 points. Because service-to-service communication needs management.

- Message queues cost 15 points. Because synchronous calls between services will kill you.

If you spend 80 points on architecture, you only have 20 points left for your actual product. Microservices are for companies that have overflow budget—not for startups that are starving for engineering time.

I've watched teams burn their entire complexity budget on infrastructure that Netflix uses, then wonder why they can't ship features. Netflix can afford to spend 60 points on architecture because they have 10,000 engineers generating budget. You have 8 engineers, and you just spent your entire allocation on Kubernetes before writing a line of business logic.

The Prerequisites

Microservices add complexity. That complexity is only justified when you have problems that simpler architectures can't solve. Before considering microservices, you need:

Team scale requiring independence. If you have three developers, microservices will slow you down. The coordination overhead exceeds any benefit. In my experience, you need at least 20-30 engineers before the organizational benefits of microservices outweigh the technical costs.

Deployment frequency requirements. If you deploy weekly, a well-structured monolith is fine. Microservices shine when different parts of your system need to deploy at different cadences (when the payments team needs to ship daily while the reporting team ships monthly.

Genuinely different scaling needs. Your search service handles 10,000 requests per second while your admin dashboard handles 10. Scaling them together wastes resources. Scaling them separately requires boundaries.

Mature DevOps capabilities. Microservices require sophisticated deployment, monitoring, and debugging infrastructure. If you can't deploy a monolith reliably, you definitely can't manage 50 services.

Without these prerequisites, microservices are a solution to problems you don't have.

When Organization Forces Architecture

Conway's Law says system design mirrors organizational structure. This cuts both ways: you can fight your org structure with architecture, or you can embrace it.

Microservices make sense when your organization is already distributed. If you have autonomous teams in different time zones with distinct domains, forcing them to coordinate on a monolith creates friction. The architecture naturally follows the organization.

At one company I worked with, three teams in three countries shared a monolith. Every deploy required coordination across time zones. Simple changes took weeks. Splitting into services aligned with team boundaries—not technical boundaries —reduced friction dramatically.

Microservices are an organizational tool more than a technical one. Use them when team autonomy is more valuable than shared code.

The Conway's Law inversion: Don't use microservices to fix your culture. If your teams can't talk to each other, splitting their codebases won't help. It will just turn organizational dysfunction into network latency. I've watched companies adopt microservices hoping to solve communication problems, only to discover they'd created new communication problems with higher failure modes. The teams still couldn't coordinate—now they couldn't coordinate across network boundaries.

The Right Boundaries

Most microservices failures come from wrong boundaries. Services split by technical layer (data service, business logic service, API service) create distributed monoliths (all the complexity of microservices with none of the benefits.

Boundaries that work:

Business capability alignment. Each service owns a complete business capability: payments, inventory, user management. The service can evolve independently because it owns its entire domain.

Data ownership. If two services need to share a database, they probably aren't separate services. True microservices own their data. This constraint forces careful thinking about boundaries.

Deployment independence. A service that can't deploy without coordinating with other services isn't providing microservices benefits. If changing service A requires updating service B, you've built a distributed monolith.

I've found Domain-Driven Design's bounded context concept useful here. Each service maps to a bounded context—a clear boundary where a particular domain model applies. Cross-context communication happens through well-defined interfaces.

Start With a Monolith

The most successful microservices architectures I've seen started as monoliths. Martin Fowler's "MonolithFirst" principle captures this: the team builds the product, understands the domain, and only then extracts services where the boundaries become clear.

Premature decomposition is the microservices killer. You guess at boundaries before understanding the domain. You split things that should be together. You couple things that should be separate. Fixing these mistakes in a distributed system is harder than fixing them in a monolith.

The rewrite trap applies here too. Don't extract services speculatively. Extract them when you feel the pain that extraction solves: teams stepping on each other, scaling bottlenecks, deployment conflicts.

The pattern that works: monolith with clear module boundaries, then extract modules to services when you have concrete reasons. The module boundaries become service boundaries. The internal interfaces become APIs.

Communication Patterns That Scale

Synchronous HTTP calls between services look simple but create problems at scale. Service A calls B calls C calls D (one slow service cascades failures through the system. I've watched entire platforms go down because one service became slow.

Patterns that work better:

Asynchronous messaging. Services communicate through message queues. The caller doesn't wait for a response. Failures are isolated. This requires thinking differently about operations that feel like they should be synchronous.

Event sourcing. Services emit events about what happened. Other services subscribe to events they care about. No direct coupling between producer and consumer.

API gateways for external traffic. A single entry point handles authentication, rate limiting, and routing. Internal services don't need to duplicate this logic.

Circuit breakers for synchronous calls. When you must make synchronous calls, circuit breakers prevent cascade failures. If a downstream service is failing, stop calling it and fail fast.

The goal is isolation. Each service functions (perhaps in degraded mode) when other services are unavailable.

Operational Maturity Requirements

Microservices require operational capabilities that monoliths don't. Before decomposing, ensure you have:

- Distributed tracing: Following a request across services requires tooling. Without it, debugging is nearly impossible.

- Centralized logging: Logs scattered across 50 services are useless. You need aggregation and correlation.

- Service discovery: Services need to find each other without hardcoded addresses.

- Automated deployment: Deploying 50 services manually doesn't scale. You need CI/CD for each service.

- Health monitoring: Each service needs health checks and alerts. Multiplied across services, this requires sophisticated infrastructure.

If these capabilities don't exist, build them before decomposing. Operating microservices without proper observability is flying blind.

The Modular Monolith Alternative

Between monolith and microservices sits a middle ground: the modular monolith. Clear module boundaries, enforced interfaces, but deployed as a single unit.

This gives you:

- Simple deployment and debugging

- No network latency between components

- Shared data access without API overhead

- Clear boundaries that could become services later

Many teams would be better served by a well-structured modular monolith than a poorly-implemented microservices architecture. The modular monolith preserves the option to extract services without paying the distributed systems tax upfront.

Shopify runs a massive modular monolith that processes billions of dollars in transactions. So do many successful companies. "Monolith" doesn't mean unstructured mess—it means single deployment unit with clear internal boundaries.

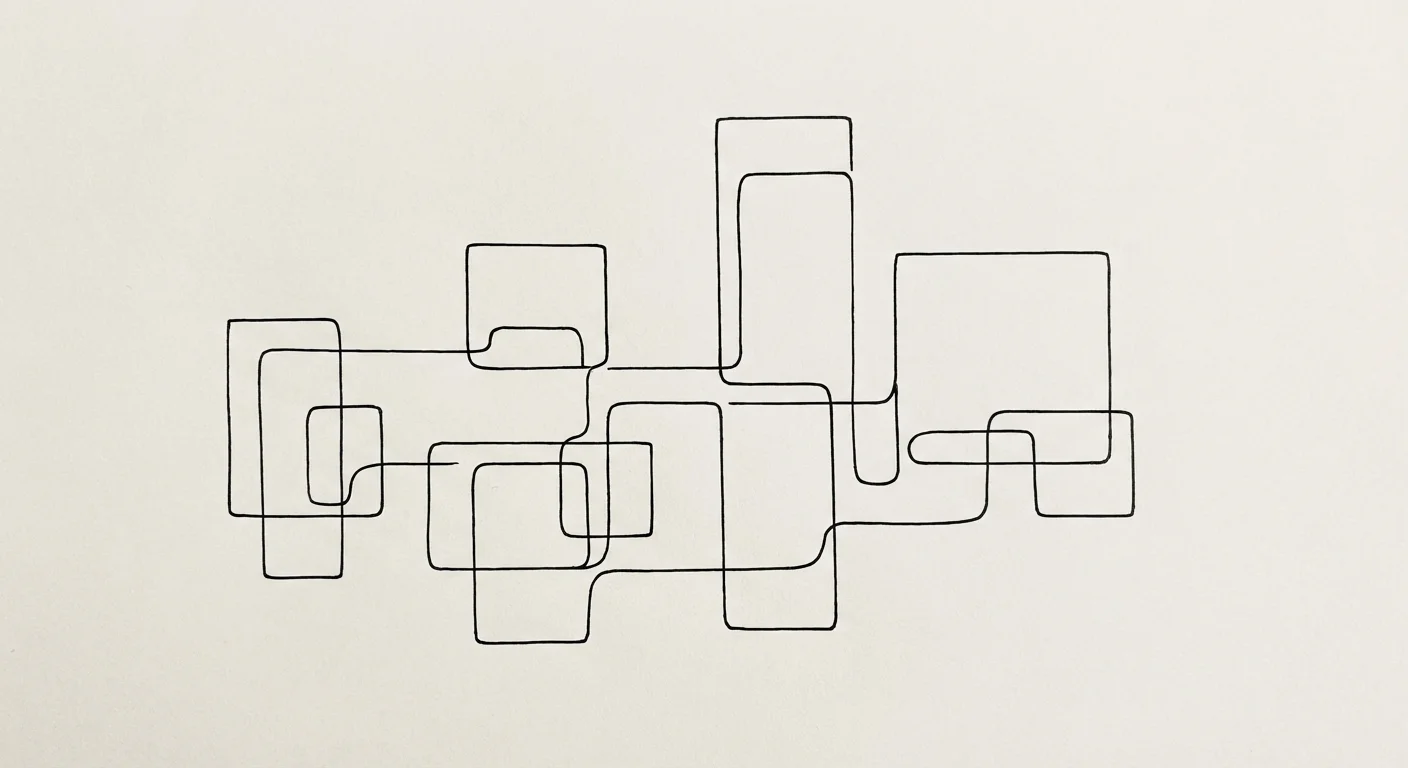

Complexity Budget Calculator

You have 100 points. Spend them wisely.

Quick Decision Guide

| Your Situation | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| <20 engineers, weekly deploys | Monolith (modular structure) |

| 20-50 engineers, same codebase | Modular monolith with clear boundaries |

| 50+ engineers, teams stepping on each other | Consider microservices for high-conflict areas |

| Components with 100x different scale | Extract the outliers as services |

| No CI/CD, manual deploys | Fix DevOps first, architecture second |

| Distributed teams, different cadences | Services aligned to team boundaries |

The Bottom Line

Microservices make sense when you have team scale requiring independence, different deployment cadences, genuinely different scaling needs, and mature DevOps capabilities. Without these conditions, you're adding complexity for its own sake.

Start with a monolith. Understand your domain. Extract services when you feel the pain they solve, not before. Get the boundaries right: business capabilities, not technical layers. Invest in operational tooling before you need it.

The question isn't "should we use microservices?" It's "do we have the problems microservices solve, and do we have the capabilities to operate them?" Answer honestly, and the architecture decision becomes obvious. For a complete decision framework, see the Microservices Decision Guide.

"Microservices are an organizational tool more than a technical one. Use them when team autonomy is more valuable than shared code."

Sources

- Martin Fowler: Monolith First — The case for starting with a monolith

- ThoughtWorks: Microservices and Evolutionary Design — Patterns for service decomposition

- Shopify Engineering: The Modular Monolith — How Shopify structures their monolith

Architecture Review

Choosing between monolith and microservices? Get objective analysis from someone who's built both successfully.

Get Assessment