Over $20 billion in missed exits. That's the combined acquisition value of the products I built before the companies that built them: WhatsApp ($19B), Instagram ($1B), and concepts like BitTorrent and OnlyFans. Over 45 years, I kept building things that later emerged as billion-dollar companies - and never shipped them. Here's the truth about why builders fail to become founders.

Ship or kill projects within 90 days. Don't let inventions languish—the window closes. Perfect is the enemy of shipped.

I'm not writing this for sympathy or to make some point about timing. The pattern itself is fascinating - and useful for anyone who builds things. These weren't failed businesses. They were working software I built to explore and solve problems during my 45 years in tech. The insight? Recognizing when something you built might matter to others.

Why I Build Things

Context matters: I invent things for fun. First Round's analysis shows that shipping and iterating matters more than the idea itself. I build platforms and tools to understand how something works, to scratch an intellectual itch.

When I built ECHO, I wasn't thinking about business models - I was thinking "can I make a push system that's truly stateless and scalable?" The challenge itself was the reward.

Friends would say "you should release this." But the gap between a fun project and a production-ready product is enormous. Documentation, error handling, edge cases, onboarding, support. That gap is where most of these projects stayed.

The List

| What I Built | What It Became | Their Outcome | Why I Didn't Ship |

|---|---|---|---|

| File Scatter | BitTorrent | 35% of all internet traffic (2004) | Perfectionism |

| ECHO | $19 billion acquisition (2014) | Overthinking ("too simple") | |

| ECHO auth tokens | Similar to JWT (RFC 7519) | Industry standard (2015) | Bundled with ECHO, never extracted |

| Scorpion | Subscription content economy | OnlyFans: $6.6B gross (2023) | Let someone else decide |

| Trivlet | HQ Trivia | 2.38M concurrent players (2018) | Wrong pivot from ECHO |

| Razzibot | $1 billion acquisition (2012) | Wrong form factor |

That's not a list of ideas. That's a list of working software that I built, tested, and then... didn't ship.

File Scatter (1980s)

When you run bulletin boards connected by FidoNet, you develop a specific problem. How do you move big files across a network of nodes connected by phone lines?

Phone calls cost money. 2400 baud modems are slow. A 5MB file could take hours to transfer. If the call dropped, you started over.

The insight: you don't need to transfer the whole file from one source. Split it into chunks, distribute different chunks to different nodes, let everyone share what they have.

File Scatter did exactly that. Smart routing preferred local BBSs to save long-distance costs. Transfers resumed from the last chunk. Downloaded a chunk? Now you're a source for it. Popular files practically distributed themselves.

What happened: On July 2, 2001, Bram Cohen released BitTorrent. Same core concepts - files split into pieces, distributed sources, progressive availability, verification. By 2004, BitTorrent accounted for 35% of all internet traffic.

I used File Scatter on my own BBSs and shared it with a few friends. I never released it publicly because it wasn't "done enough."

ECHO (2000s-2014)

This one taught me the most.

ECHO started as a concept I'd been developing since the early 2000s. Real-time messaging, presence indicators, cross-platform support, group messaging, read receipts. Stateless servers, custom binary protocol for mobile networks. In 2014 at ZettaZing, I tested it at scale: 3,000+ AWS instances.

ECHO also used an approach similar to what became JWT. When you logged in, you got a token with user ID, expiration, and cryptographic signature - any server could verify without hitting a database. RFC 7519 was published in 2015. I had the concept years earlier.

The fatal thought: I looked at ECHO and thought "This is too simple. It's just... chat. Nobody's going to pay for chat."

So I started adding complexity. Enterprise features. Admin consoles. Developer APIs. Permission hierarchies. Integration frameworks. Each feature made sense in isolation. Each feature made the product harder to ship.

I was building a platform when I should have been shipping a product.

What happened: In January 2009, Jan Koum bought an iPhone and decided to build an app. The original WhatsApp concept? Let users set status messages. That's it. When they added messaging, the app exploded.

In February 2014, Facebook bought WhatsApp for $19 billion. For a messaging app. The thing I thought was "too simple."

Simple wasn't a weakness. Simple was the entire value proposition. We conflate complexity with value, but users just wanted to message friends.

Scorpion (Mid-1990s)

This story has a different lesson.

In the dial-up era, streaming didn't exist. If you wanted content, you downloaded it. And downloading was slow - you'd start before work and hope it finished by the time you got home. Connections dropped constantly.

Scorpion was a subscription service with a desktop client. Set your preferences, and while you were at work, it downloaded content matching your interests. $5/month or $50/year. The content was adult - one of the few things people would pay for online in the mid-1990s.

The technology was solid: intelligent preference learning, bandwidth optimization, resumable transfers, automatic storage management. The business model made sense. I had spreadsheets. Numbers worked.

What killed it: I showed Scorpion to a business partner. His response: "This will ruin your reputation."

Not "the technology doesn't work." Not "the business model is flawed." Just: "This will ruin your reputation."

I was young. I wanted to be taken seriously in tech. So I listened. I didn't ship.

What happened: OnlyFans, founded in 2016, processed $6.63 billion in gross payments in 2023. The subscription content economy - the exact model I built - turned out to be worth tens of billions.

The lesson: I confused counsel with permission. My partner offered a valid opinion. But I treated it as a veto. He wasn't putting in the work or taking the risk. I let his opinion determine my path.

Trivlet (Built on ECHO)

Remember ECHO, my messaging platform? Here's what I actually built on it instead of shipping messaging.

Trivlet was a real-time trivia platform supporting unlimited concurrent players. Questions appeared on everyone's screen simultaneously - not "within a few seconds." Answers were timestamped server-side. Results appeared instantly. Live leaderboards updated as answers came in.

The technical problems were genuinely hard: true simultaneity across millions of clients, instant aggregation of answers, cheating prevention. I was proud of solving them.

The reasoning: "Messaging is boring - everyone has it." "Trivia has a clearer business model." "This is technically interesting." "Nobody else is doing this."

What happened: HQ Trivia launched in 2017. Live trivia games, twice daily, real cash prizes. At peak, 2.38 million concurrent players. The exact concept Trivlet could do.

HQ Trivia shipped. They added the hook (real money). They created appointment viewing (specific times). They embraced imperfection (servers crashed, they fixed in production). They had a personality (Scott Rogowsky). They raised $15 million.

I had the right technology and built trivia on top instead of shipping the simpler product: messaging. I was building to impress engineers, not serve users.

Razzibot (Late 2000s)

Razzibot was a photobooth system with filters, effects, and instant social sharing. Essentially Instagram's feature set in physical form, before Instagram launched in October 2010.

Picture a photobooth at an event. You step in, take a photo, swipe through filters - vintage, high contrast, warm tones, black and white. Each previews instantly. Pick one, add effects, hit share. Your photo posts to Facebook or Twitter, and you walk away with a physical print.

I understood what would later make Instagram successful: filters make everyone a photographer. A good filter transforms a mediocre phone photo into something intentional, artistic, shareable.

The fatal constraint: Razzibot was a photobooth. A physical object. It needed to be transported, set up, staffed. It could only be in one place at a time. I was selling hardware when I should have been selling software.

What happened: Instagram launched October 6, 2010. iPhone-only, free, dead simple: take a photo, apply a filter, share. Within two hours, servers struggled. Within two months, 1 million users. April 2012: Facebook acquired it for $1 billion. Thirteen employees, no revenue.

The features were identical. The delivery mechanism was everything. A photobooth reaches people at events. An app reaches everyone, everywhere, all the time.

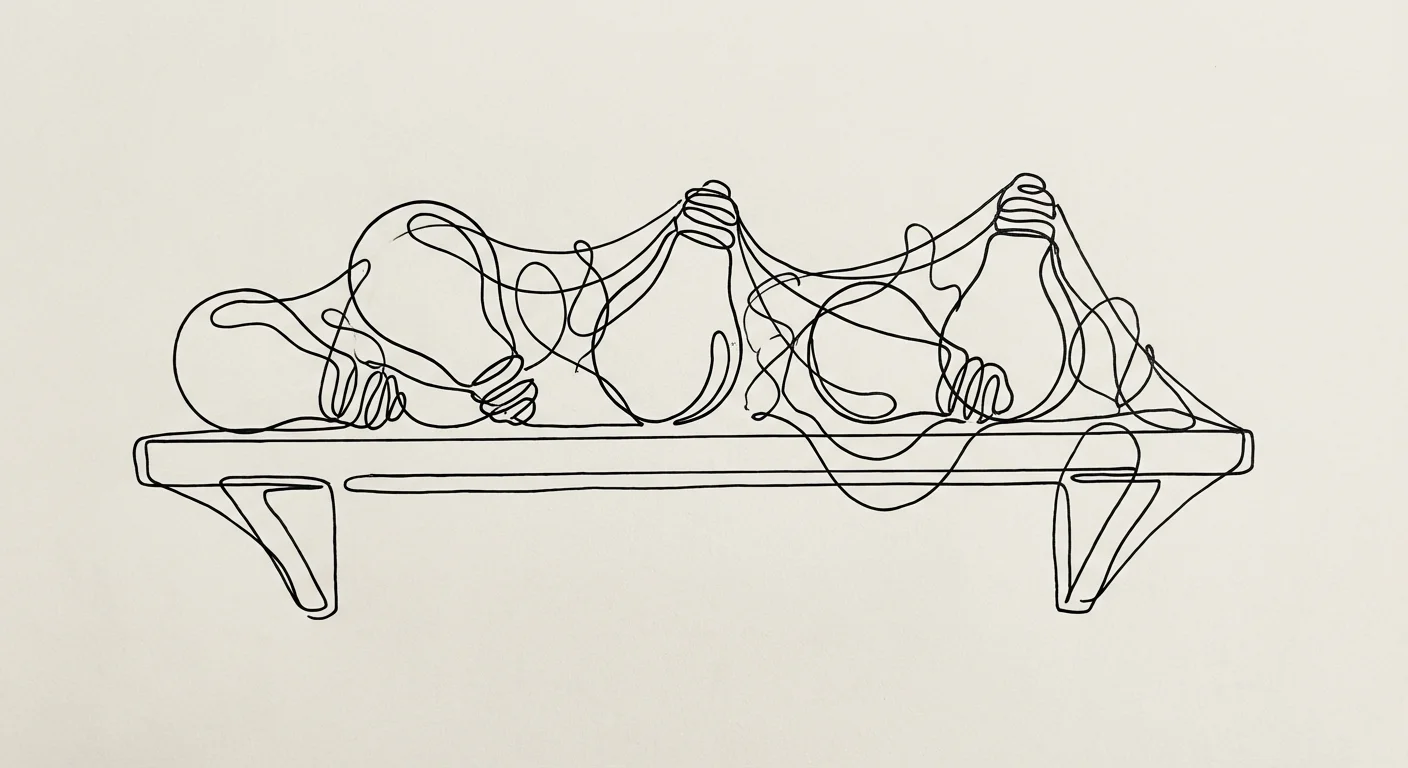

Ship It or Kill It Timer

How long has your project been in development without shipping?

The Patterns

Looking at this list, I see distinct patterns - and recognizing them is the valuable part:

Perfectionism (File Scatter): The code worked. But it wasn't "done." There was always one more edge case, one more refactor. Software is never done. As research on innovation timing consistently shows, the window for first-mover advantage is often narrow - perfectionism can be the difference between market leadership and obscurity. Shipping is a decision, not a state of completion.

Overthinking (ECHO): I had something valuable and convinced myself it wasn't enough. I conflated complexity with value. Simple won. Founder ego can manifest in many ways - including convincing yourself your simple solution isn't good enough.

Letting others decide (Scorpion): I gave someone else veto power over my judgment. There's a difference between seeking counsel and seeking permission.

Wrong pivot (Trivlet): You have something valuable, but instead of shipping it, you use it to build something "better." You're still building, still shipping something. Just the wrong thing.

Wrong form factor (Razzibot): The idea is right but the medium is wrong. Understanding the market matters as much as building the product.

I've written about similar patterns with RUM, my challenge-response spam filter—another working system I built and didn't release, watching others commercialize the same concept.

What I Did Ship

The unshipped ideas are only half the story. I also ran a successful consulting business for over a decade - real problems for real clients:

- Core Logic Software (1996-2004) - Platforms for AirTouch Cellular, Preston Gates & Ellis, The Sci-Fi Channel. Real code, real deadlines, real checks clearing.

- Workbench at MSNBC - Publishing platform reaching millions of readers daily

- ECHO at ZettaZing - Tested at 30M concurrent connections

- Voice AI for government - US Coast Guard and DHS

When I shipped, good things happened. The pattern is clear.

When Not Shipping Is Right

I'm not saying every project should ship. Holding back makes sense when:

- You're genuinely exploring, not building a business. Learning projects have value independent of market outcomes. Not everything needs to be a startup.

- The market isn't ready. Sometimes timing matters more than execution. Being ten years early is functionally the same as being wrong.

- The personal cost exceeds the potential gain. Scorpion's advisor had a point about reputation. The calculation just needed to be mine, not his.

But for most builders with working prototypes, the default should be shipping. The lessons from users outweigh the comfort of perfection. Make "not shipping" a conscious choice, not a drift.

The Bottom Line

If you're a builder who recognizes yourself in this list, here's what I've learned:

Ship this week. Not when it's ready. Whatever you have, put it in front of users. Their feedback is worth more than another month of polishing.

Complexity is not value. If your product is simple and solves a problem, that's not a weakness. Users want their problem solved, not your elegant architecture.

Your judgment matters. Get input from people you trust. Then make your own decision. You understand what you're building better than advisors who aren't in the trenches.

Time matters. Every month you don't ship is a month someone else might.

The best time to ship was years ago. The second best time is now.

"The best time to ship was years ago. The second best time is now."

Sources

- Wikipedia — BitTorrent traffic: - 35% of internet traffic by 2004

- CNN — WhatsApp acquisition: - $19B, February 2014

- Wikipedia — Instagram acquisition: - $1B, April 2012

- Expanded Ramblings — HQ Trivia peak: - 2.38M concurrent, March 2018

- Variety — OnlyFans financials: - $6.63B gross, 2023

- IETF RFC 7519 — JWT RFC: - Published May 2015